Open Enrollment in Colorado: Market Benefits, Market Challenges

- Eric Mason

- Sep 30, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Oct 13, 2025

Open enrollment has become one of the most consequential features of Colorado’s education system, and its impact is growing more urgent by the year. As districts face post-pandemic enrollment declines, rising pressure to consolidate schools, and debates over how best to serve families across lines of income and geography, open enrollment sits at the center of Colorado’s policy crossroads. It promises families access to better-fit schools and creates market incentives for districts to innovate—but it also raises thorny questions about equity, funding stability, and the long-term viability of urban core districts. Understanding how these dynamics are playing out in Colorado today offers lessons not just for the state but for the national conversation on school choice.

State policies around open district enrollment were formulated to give opportunities to families seeking a batter place for their student to thrive. In my experience, efficacy of choice is driven by several factors, not the least of which is knowledge that the choice exists. Although my daughters attended our local community elementary school, when they moved into the middle years, we lived just on the line between our home district and the neighboring district. A high performing middle school in the neighboring district was less than 1 minute away. The middle school in our home district to which my children were assigned was a fine middle school, but it was nearly 15-20 minutes away. We choiced our children into the closest middle school. Once we made that choice, the decision was permanent - not legally but practically. Our children built friendships, participated in sports and choir, and when they aged out of the middle school, we naturally chose to send them to the high school where most of the children they knew matriculated. Convincing our daughters to leave their friends and attend a high school where they knew only a few children did not even occur to us as a choice. Their "home" high school was much closer and did not require us to get military passes and pass through a base security checkpoint on the 30-40 minute drive, yet their path through high school was cemented by our middle school choice.

There are long term ramifications to open enrollment. As I discuss below, there are financial ramifications for the school systems, and there are personal ramifications for the families involved. Within these conversations there are, and were when I led as a district administrator, inevitable discussion about the very nature of district boundaries and divided resources. In the Colorado Springs metro area, there are 11 school districts ranging in enrollment size from less than 5,000 students to more than 30,000 (not including independent charter school systems and private schools). Each district maintains its own infrastructure, transportation, administration, special services, IT support, and software infrastructure. Each district pays for its own curriculum, software, and standardized testing systems. Often, families that choice into other districts must provide their own transportation to school and those families cannot vote in the bond elections or school board elections where their own children attend school. The policies and impacts around open enrollment are complex, and complex social systems are wickedly complex to study.

Below, I examine just a couple of topics related to open enrollment, and as with all interesting topics, there are open questions left to answer. One of those questions is how can Colorado—and by extension, other states—maximize the benefits of open enrollment while mitigating its inequitable and sometimes destabilizing effects on legacy districts, funding systems, and community cohesion?

Research on Open Enrollment in Colorado

Open enrollment has been a defining feature of Colorado’s education system since the 1990s, making it one of the most studied states in the nation on this issue. Research consistently highlights both the opportunities and the challenges that result from allowing families to enroll children in schools outside their home district.

In Colorado, open enrollment refers to the policy that permits students to attend public schools outside of their assigned neighborhood or residential district. Today, about 13.1% of Colorado’s K–12 students enroll in schools beyond their district of residence, reflecting one of the highest rates of interdistrict mobility in the nation (Colorado Department of Education, 2023). Over time, participation in open enrollment has steadily increased, as families seek specialized programs, academic advantages, or simply schools they believe are a better fit.

Studies by Lavery and Carlson (2015) and Garcia (2021) show that open enrollment in Colorado disproportionately benefits more advantaged families who have the resources to navigate transportation and application processes. Students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch are less likely to transfer successfully, and when they do, they are less likely to persist in their new districts. Analyses of enrollment flows suggest that interdistrict choice can exacerbate socioeconomic stratification (Carlson, Lavery, & Witte, 2011). Higher-income families are more mobile, leaving higher-poverty districts with increased concentrations of need and fewer resources. Garcia’s (2021) network analysis documented over $7.7 billion in state funding redirected across districts between 2003 and 2017 due to open enrollment, underscoring how choice reshapes district finances and governance.

National research offers mixed results. While some studies find academic gains for students who transfer into higher-performing districts, others caution that benefits are uneven and often concentrated among families with the means to participate fully (Winters, Clayton, & Carpenter, 2017). Work by Vasquez Heilig, Brewer, and Williams (2019) shows that charter and choice policies can intensify racial and economic segregation. Even after controlling for local demographics, charter schools and open enrollment systems often result in higher levels of isolation. Nationally, choice tends to accelerate suburban growth while destabilizing urban core districts—mirroring patterns now visible in Colorado Springs.

Overall, the research base suggests that open enrollment creates important opportunities for families but also poses systemic challenges: shifting resources, reshaping demographics, and increasing pressure on urban districts. Colorado serves as a case study in both the promise and the market challenges of broad school choice. For policymakers, the question is not whether to allow choice—it is how to manage its consequences so that all students, regardless of economic advantage, can benefit.

Net Flow and Student Poverty in Colorado’s Largest Districts

When we examine the 20 largest school districts in Colorado, two dynamics stand out: the net flow of students in or out of each district and the concentration of students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch (FRL), a common indicator of student poverty.

The chart below (Figure 1) of Colorado’s 20 largest districts reveals how student mobility directly redistributes dollars over time. The blue bars show net student inflows and outflows, while the red dots indicate the corresponding gains or losses in base per-pupil funding. Districts such as Academy 20 and Falcon 49 sit to the left, with strong net inflows of students and funding boosts of over $30 million each. By contrast, Colorado Springs D11, Aurora (Adams-Arapahoe 28J), and Cherry Creek appear on the right, experiencing sharp outflows that translate into tens of millions of lost dollars. This visualization underscores the fiscal reality of open enrollment: every student who leaves eventually takes their state allocation with them, shifting resources from one district to another and creating both winners and losers in the market for public education. In short, the chart shows that student choice is reshaping Colorado’s education landscape, not just in terms of dollars but in terms of who stays and who leaves.

Why Funding Losses Don’t Happen Overnight: When students leave a district, Colorado’s school finance law cushions the impact. Instead of tying funding only to the current year’s enrollment, the state uses multi-year averaging of pupil counts (often four- or five-year averages) to “smooth” sudden changes. This means districts don’t immediately lose every dollar tied to departing students—giving them time to adjust their budgets. But over time, persistent outflows still erode a district’s funding base. As adopted in HB 24-1448, the new school finance formula provides funding based on the greater of the district or state Charter School Institute (CSI) school current year student count, or an average of the current year count and one, two, or three prior year counts (a provision known as four-year averaging). For purposes of calculating total program through the phase in period, the old formula maintains a five-year averaging provision. Read more: Chalkbeat Colorado: School finance bill clears House Education Committee

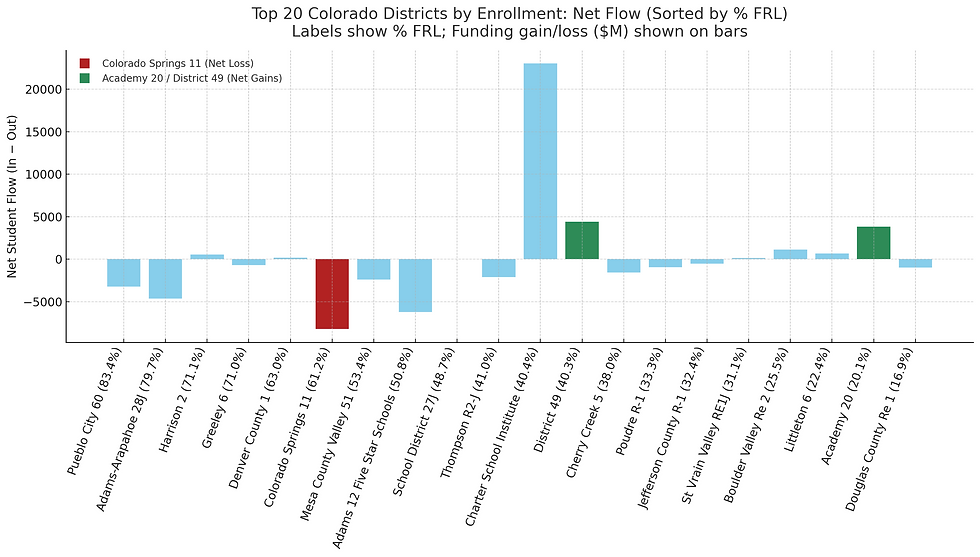

The chart below (Figure 2) highlights how districts with high student inflows or outflows also tend to show significant variation in their FRL percentages. On the left of the chart are districts like Denver Public Schools, which maintain a slight positive inflow of students despite enrolling a relatively high percentage of FRL-eligible students. By contrast, districts such as Adams-Arapahoe 28J (Aurora), with one of the highest FRL rates among large districts, see substantial student outflows. This suggests that families who can exercise choice often leave higher-poverty districts, potentially reinforcing demographic and economic divides (Lavery & Carlson, 2015).

At the far right of the chart, districts with the largest net losses of students are almost all those serving higher proportions of FRL students. The pattern points to a challenge that has been consistent across research on open enrollment in Colorado: interdistrict choice disproportionately benefits more advantaged families who have the resources to navigate transfers and transportation (Garcia, 2021). Families in high-poverty districts may have fewer real options, leading to a concentration of poverty in the districts that already face the steepest challenges.

The red line on the chart traces funding gains and losses tied to these enrollment shifts, but the FRL labels remind us that this is more than a fiscal story. Every student who leaves represents both a resource and a need shifting across the state. Districts with higher FRL rates often face greater demands for academic support, counseling, and wraparound services—yet these are the same districts more likely to experience enrollment losses and the corresponding reductions in per-pupil funding. In the middle of the chart, suburban districts such as Jefferson County and Douglas County show modest or negative net flows, paired with lower FRL percentages than their urban neighbors. Meanwhile, districts like Cherry Creek—long considered an academic draw—now show a sizable net outflow of students, even as their FRL rate remains lower than many peer districts. Open enrollment should be celebrated as a mechanism that expands opportunity and drives improvement, but policymakers must ensure that its benefits are accessible to all families, not just those with greater means.

Colorado’s experience underscores a key tension in state school choice policy nationwide: choice can catalyze innovation, but it also forces difficult trade-offs about how to fund districts equitably in a competitive market. Policymakers in states like Arizona, Florida, and Minnesota are wrestling with similar questions—how to preserve opportunity while preventing system fragmentation. Yet this does not diminish the value of open enrollment itself. The system creates competition, encourages innovation, and ensures that districts remain responsive to family preferences. These market benefits are real and significant—but they also come with market challenges. Districts that lose students must adjust by closing or consolidating schools, reinvesting in specialized programs, and ensuring that those who remain are not left with diminished opportunities. States and districts must have proactive plans in place to manage these shifts equitably.

Older school districts losing students to open enrollment face a fiscal vise: revenue drops quickly with each departing pupil, but costs seldom shrink in tandem. In most states, per-pupil funding follows the student, so when enrollment declines the district’s income falls immediately soon after [1]. However, districts cannot instantly scale down expenditures because many costs are fixed or stepwise: buildings still need heating and maintenance, principals and support staff remain, and certain staffing ratios must be upheld[2]. Research confirms that this dynamic creates “excess costs” for shrinking districts – one peer-reviewed study found that when students leave for other schools, districts are left paying for underused facilities and overhead that do not diminish proportionally (Bifulco & Reback, 2014[3]). Often state policies cushion the blow with temporary funding protections (e.g. hold-harmless provisions or using last year’s headcount), delaying the revenue loss[4]. But such delays can compound long-term strain: once the stop-gap funding expires, districts face a budget cliff while still saddled with legacy infrastructure and fixed obligations. National examples illustrate the challenge. Detroit’s public school system lost two-thirds of its enrollment in just seven years, leaving a vast number of half-empty schools that are costly to operate[5]. Chicago, too, enrolls around 70,000 fewer students than a decade ago yet continues to operate many aging, under-utilized buildings – an expensive imbalance that leaders have been slow to address (Joseph, 2025[6]). In short, declining-enrollment districts cannot easily “right-size” their expenses in the short run, so they end up spending more per student on overhead, squeezing resources for educational programs. Policymakers should recognize that without adjustments, open enrollment and other choice policies can leave legacy districts with structural deficits, as facilities and administrative costs remain high even as student counts dwindle.

Colorado Springs D11: Losing Students to Neighboring Districts

No district in Colorado lost more students to open enrollment in 2023–24 than Colorado Springs District 11. With thousands of students flowing out, D11 stands as the state’s most extreme example of how open enrollment reshapes the educational map. What makes this pattern especially striking is where many of those students are going. In stark contrast, two of the state’s largest net inflow districts—Academy District 20 and Falcon District 49—border D11 to the north and east. Both are growing suburban systems with newer schools, large housing developments, and reputations for strong academic performance. Together they absorbed nearly 8,300 net new students last year. District 20 gained 3,816 students with only 20.1% FRL, making it a magnet for more affluent families. District 49 gained 4,419 students with 40.3% FRL, reflecting its rapid suburban growth and appeal across socioeconomic groups.

No district in Colorado lost more students to open enrollment in 2023–24 than Colorado Springs District 11. D11’s net outflow of –8,198 students translates into a loss of roughly $66.2 million in base per-pupil funding.

The reasons for this dynamic are complex but familiar:

Demographics and geography: D11 serves the older core of Colorado Springs, where school facilities are aging and enrollment is more heavily weighted toward higher-poverty students. By contrast, District 20 and District 49 encompass booming suburban neighborhoods with newer infrastructure and higher-income populations.

Perceptions of school quality: Families seeking advanced programs, specialized academies, or simply newer campuses often look north to D20 or east to D49.

Mobility patterns: As families move into affordable housing in these neighboring districts, open enrollment accelerates the trend by allowing others to follow without physically relocating.

Funding implications: D11’s net outflow of –8,198 students translates into a loss of roughly $66.2 million in base per-pupil funding. District 20’s net inflow brings in about $30.8 million, while District 49’s inflow adds nearly $35.7 million. These shifts show how enrollment patterns directly redistribute resources across district lines (Colorado Department of Education, 2023).

The result is a reinforcing cycle. D11 loses enrollment, and with it, millions of dollars in per-pupil funding. At the same time, its neediest students—those qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch—become a larger share of the district population, increasing the demand for services even as resources shrink. Neighboring districts, meanwhile, grow their funding base and attract a more socioeconomically diverse set of families.

In this sense, D11’s story illustrates a core tension in Colorado’s choice system: while open enrollment expands opportunity for individual families, it can also affect urban core districts. The challenge is not to restrict choice but to manage it effectively. Districts and states must be prepared to merge or close schools when necessary, reinvest in program offerings, and guarantee that all students—regardless of economic advantage—can benefit from the opportunities that open enrollment creates.

Contact and Services

If you are a school leader, policymaker, or education advocate interested in understanding the impacts of open enrollment or applying research insights to your own district, I invite you to connect with me. At NovaEventus ECM, we provide services in education research, program evaluation, data analysis, and strategic planning. Our work helps districts and states make evidence-based decisions, design effective improvement plans, and communicate results clearly to stakeholders. You can reach me at eric@novaeventus.com to explore how NovaEventus ECM can support your goals.

*The Charter School Institute (CSI) is Colorado’s statewide charter authorizer and was the single largest net gainer of students in 2023–24. Unlike traditional districts, CSI is not tied to neighborhood attendance boundaries. Instead, it oversees a network of charter schools across the state, each of which accepts students through open enrollment regardless of their district of residence.

References

Carlson, D., Lavery, L., & Witte, J. F. (2011). The determinants of interdistrict open enrollment flows: Evidence from two states. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(1), 76–94. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373711398120

Colorado Department of Education. (2023). 2023–24 Pupil membership and non-resident student reports. https://www.cde.state.co.us/cdereval/2023-2024pupilmembership

Garcia, M. (2021). Network exploration of interdistrict school choice over time in a mandatory open enrollment state. Teachers College Record, 123(9), 171–198. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/01614681211052006

Lavery, L., & Carlson, D. (2015). Dynamic participation in interdistrict open enrollment. Educational Policy, 29(5), 746–779. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1063739

Vasquez Heilig, J., Brewer, T. J., & Williams, Y. (2019). Choice without inclusion? Comparing the intensity of racial segregation in charters and public schools at the local, state, and national levels. Education Sciences, 9(3), 1–17. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7102/9/3/205

Winters, M. A., Clayton, G., & Carpenter, D. M. (2017). Are low-performing students more likely to exit charter schools? Evidence from New York City and Denver, Colorado. Economics of Education Review, 60, 29–50. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272775716306677?via%3Dihub

Bifulco, R., & Reback, R. (2014). Fiscal impacts of charter schools: Lessons from New York. Education Finance and Policy, 9(1), 86–107. DOI: 10.1162/EDFP_a_00121

Hahnel, C., & Pearman, F. A. II. (2023, September). Declining enrollment, school closures, and equity considerations [Policy brief]. Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE).

Joseph, M. (2025, June 25). Enrollment decline: The biggest threat to public schools that no one wants to tackle. Education Commission of the States – ExcelinEd blog.

Kaput, K., Hahnel, C., & McMillan, B. (2024, September). How student enrollment declines are affecting education budgets, explained in 10 figures. Bellwether Education Partners.

Lake, R., Jochim, A., & DeArmond, M. (2015). Fixing Detroit’s broken school system. Education Next, 15(1), 20–27.

Comments